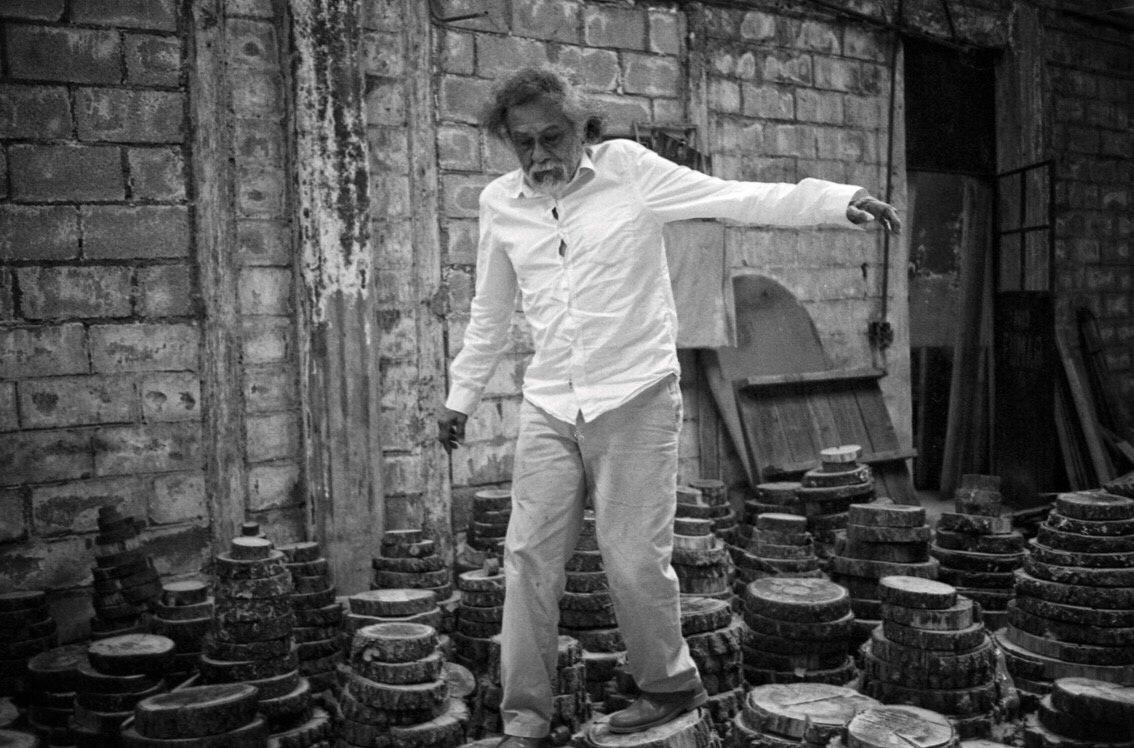

Biographical note

Francisco Benjamín López Toledo was born in Juchitán, Oaxaca, in 1940. At a very young age he found his calling in drawing and painting. He attended, still as a teenager, to the School of Fine Arts of Oaxaca and to the engraving workshop of Arturo García Bustos.

At age 17, he enrolled to the Free Engraving Workshop at the School of Design and Crafts in Mexico City. Antonio Souza baptized the artist as Francisco Toledo and helped to arrange his first individual exhibitions (at age 19) in the Antonio Souza Gallery and in the Forth Worth Center, in Texas. Towards 1960, the painter established himself in Paris, where he befriended artists such as Octavio Paz and Rufino Tamayo, while he consolidated his artistic training. Back then, he collaborated in the atelier of Stanley Hayter, one of the most influential engravers of the Twentieth Century.

During his twenties, Toledo authored works which soon grabbed the attention of the European artistic community. Proof of this are the several individual exhibitions of his work at the Kunstnerner Hus, in Oslo, Norway (1962), at the Karl Flinker Gallery, in Paris (1963), and at the Dieter Brusberg Gallery, in Hannover, Germany (1964). To these exhibitions followed others in England, New York, and Switzerland.

During his times in Paris, he began to collect several pieces of artists as important as Alberto Durero, Francisco de Goya, Eugène Delacroix, Max Klinger, Marc Chagall, Pablo Picasso, and Diego Rivera, among others, with the idea to show and disseminate universal art (this was the beginning of the Toledo/INBA collection, one of the most important collections in Latin America for its diversity and quality of the pieces it fosters).

Upon his return to Mexico, Toledo spent several seasons in his homeland, in the in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, region which he attempted to know in depth through the study of the local customs, language, and art.

In the 1970s, he began to look into certain artisanal techniques –like textile and pottery– which would influence his latter artistic creation. His social concerns led him to collaborate at the foundation of the House of Culture of Juchitan (1972). From that moment on, Toledo would become a promoter of the culture, encouraging the development and the foundation of several spaces, as well as the creation of publishing houses that would spread not only universal literature, but the Zapoteco language: Ediciones Toledo, Editorial Cálamus, and the Guchachi’ Reza (Sliced Iguana) magazine.

In 1988, upon his return from a creative stage in New York, Francisco Toledo founded the Institute of Graphic Arts of Oaxaca, a space built as a library specialized in art and several exhibition halls; its collection of books is currently of almost 60 thousand volumes distributed in two locations.

In 1993 he founded the civil association PRO-OAX (which purpose is the defense of the cultural and historical heritage of the City of Oaxaca) and which has collaborated in the creation of spaces like the Fray Francisco de Burgoa Library and the Ethnobotanical Garden, in addition to joining causes such as the defense of autonomous languages or the fight against transgenics.

At the artist’s initiative, the El Pochote film club (1992), the Centro Manuel Álvarez Bravo Photographic Center and the Jorge Luis Borges Library for the visually impaired (1996), the Eduardo Mata Sound Recordings Library (1996), the Paper Art Oaxaca Workshop (1998), and the San Agustin Etla Arts Center (2006) were founded. These cultural centers have transformed the way in which people approach culture, by establishing a close relationship with their users, a permanent updating of their collections, and a constant interaction with the national and international artistic community.

Francisco Toledo has had several retrospective exhibitions, for example, at the Museum of Modern Art, in Mexico City (1980), at the White Chapel Gallery, in London, and at the Queen Sofia Arts Center, in Madrid (2000), in addition to having presented his work at the Tate Gallery, in London, and at the Latin American Masters, in Los Angeles, among other international venues. Several art critics and writers like Henry Miller, Dawn Adès, Catherine Lampbert, Francisco Calvo Serraller, Luis Cardoza y Aragón, Teresa del Conde, and Raquel Tibol, among others, have praised the multifaceted work of the Mexican artist, stressing on the place his work occupies in the history of contemporary art.

Toledo received numerous awards in the last decades, such as the National Prize for Sciences and Arts (1998), an honorary PhD from the UABJO (2007), the Prince Klaus Award (2000), and the Right Livelihood Honorary Award (2005) in Sweden, “for his commitment and his art in favor of the protection, development, and renewal of the architectural and cultural heritage, the environment, and the community life of his native Oaxaca”.

At the end of 2014, he presented a series of sculptural pieces, including funeral urns, in memory of what happened to the 43 students of Ayotzinapa: Duelo (Mourning) (Museum of Modern Art of Mexico City). This exhibition combines his critical vision of today’s world with an aesthetic reflection on Mexican society.

Since 2015, the INBA has been the symbolic custodian of the collection of the Institute of Graphic Arts of Oaxaca and of an art collection of approximately 125,000 objects that Francisco Toledo exchanged for one Mexican peso. From this impressive selection of artistic pieces, exhibitions, materials, and reflections have emerged consolidating Oaxaca as a space of strong cultural preeminence.

Francisco Toledo always had the desire to encourage the care and development of indigenous languages, thus he founded the House in Autonomous Languages Awards, which task is to celebrate the diverse languages spoken in Oaxaca and to provide a space for new writers.

After many years he presented what could be considered his most important pictorial retrospective: Yo mismo (Myself) (IAGO, 2017), which brings together a large series of self-portraits in oil and various techniques. In this exhibition he displays a radical exploration he made of himself, without leaving aside the dialogue with the rich pictorial Western tradition. In the same year, Banamex Cultural Development concluded the publication of an extensive catalogue raisonné containing the work of five decades of the artist. This editorial corpus comprises over nine thousand works, as well as the opinions and reflections of more than a dozen writers and art critics.

For years Francisco Toledo used his scholarship as Emeritus Creator to give scholarships to children and young people with scarce resources, to buy books for different cultural spaces, and to help with different philanthropic projects. Years later, he gave up this scholarship as a way to ask the INBA to redistribute such resources to benefit Oaxacan creators. However, the painter never stopped supporting his scholarship recipients, among them young people from the Intercultural Bilingual Teacher Training School of Oaxaca.

In 2018, Toledo ve (Toledo Sees) was presented, which tells about his work in the field of design, displaying dozens of objects and utilitarian and decorative elements made in conjunction with the CASA’s artistic production department. The exhibition was held during 2021 at the Casa de México (House of Mexico) in Spain.

Francisco Toledo was always a singular creator, someone who created his own path. Different traditions converge in his work, which can be described as the deployment of original knowledge in a contemporary context, or as the constant updating of primordial elements in a work with a strong intellectual accent. Because of his themes and concerns, his work is heir to a very broad history of Mexican art and can be traced back to the pre-Columbian period. He was an exceptional reader and had a broad knowledge of universal art.

André Pieyre de Mandiargues wrote about Francisco Toledo: “I know of no other modern artist so naturally imbued with a sacred conception of the universe and a sacred sense of life, who has approached myth and magic with such seriousness and simplicity, and who is inspired with such purity by ritual and fable”.

The conjunction of life and work of the Oaxacan artist stands out as few in our country and internationally, because it remains strongly committed to the problems of our time without separation from his personal concerns. While he is linked to artists such as José Guadalupe Posada, Rufino Tamayo or Rodolfo Nieto, some scholars have suggested that Toledo’s work is heir and continuator of that of James Ensor, Paul Klee or Jean Dubuffet, and many other artists.

Francisco Toledo passed away on September 5, 2019.